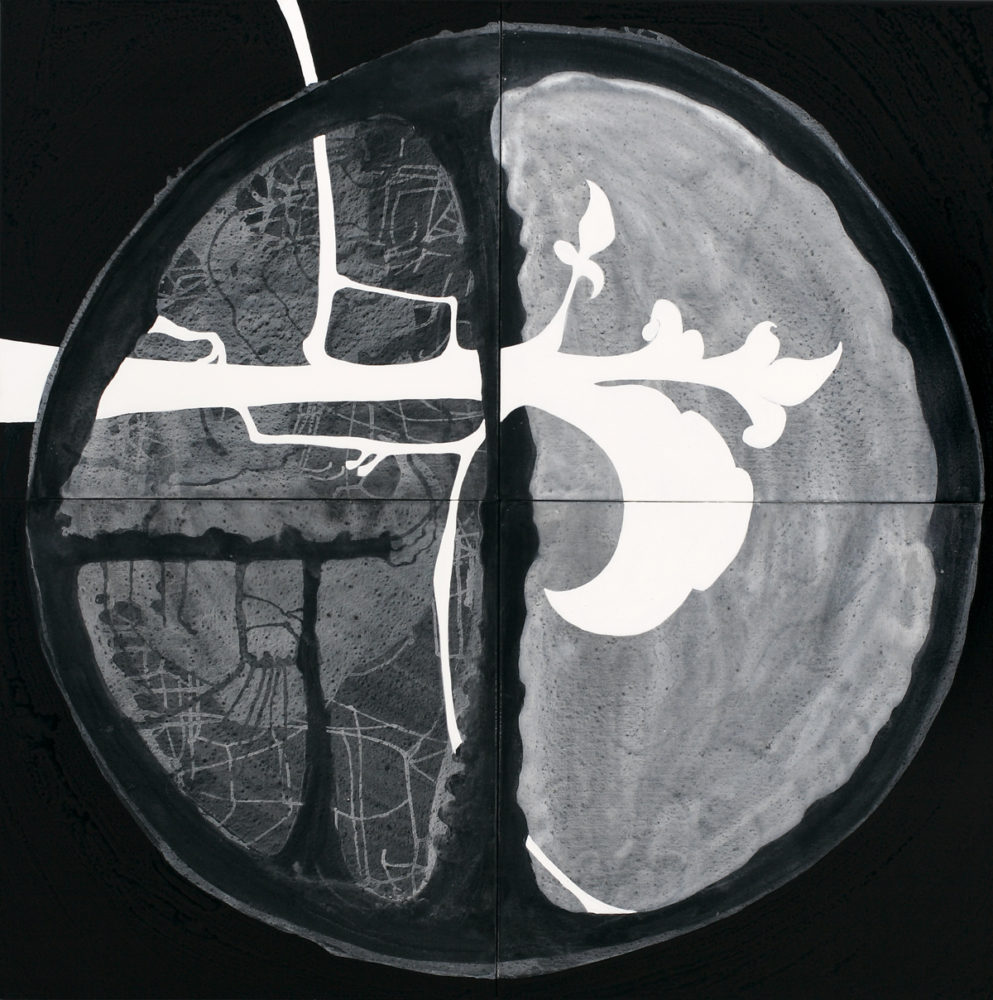

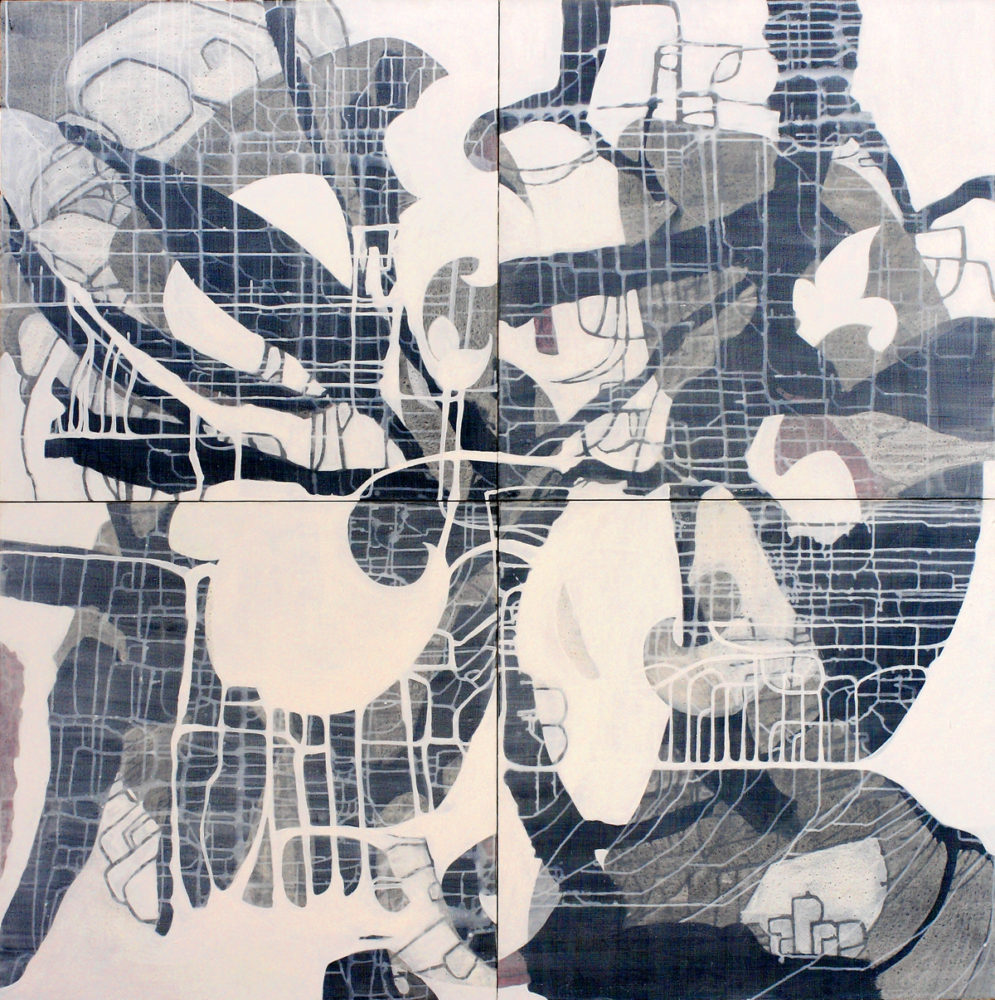

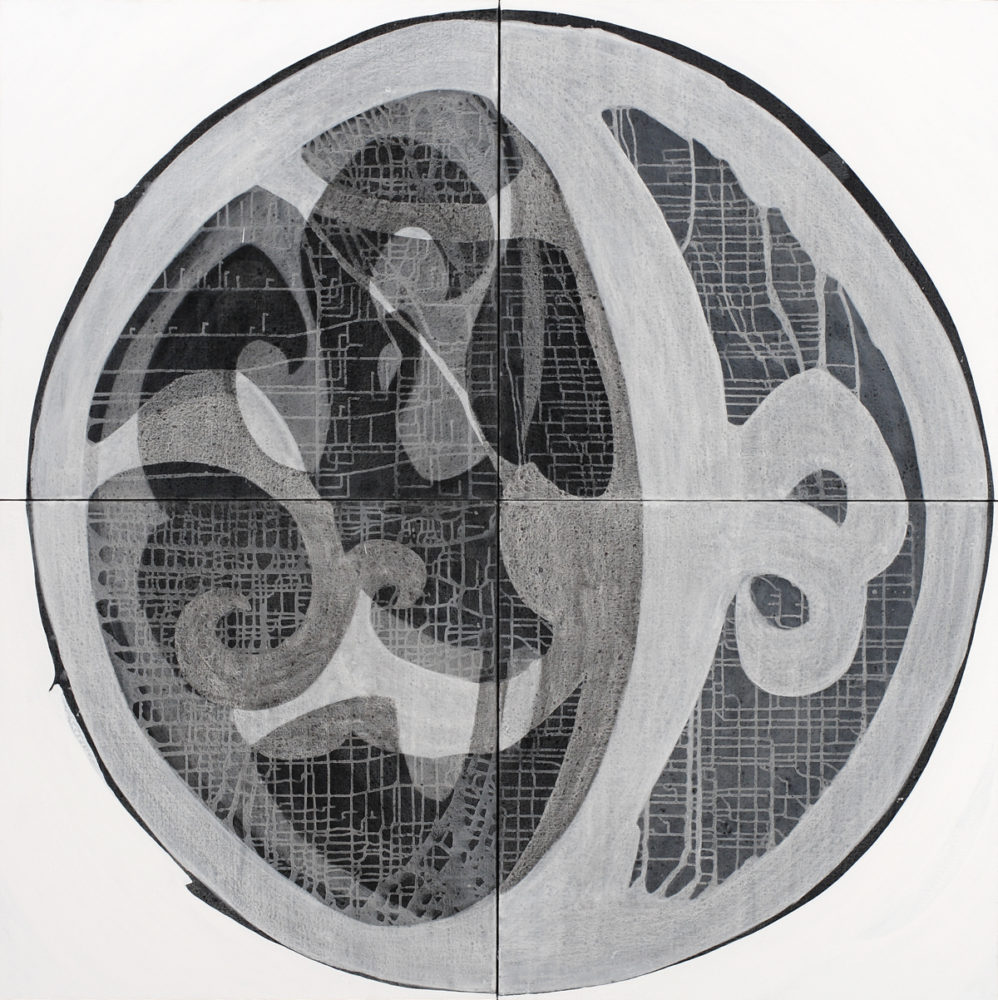

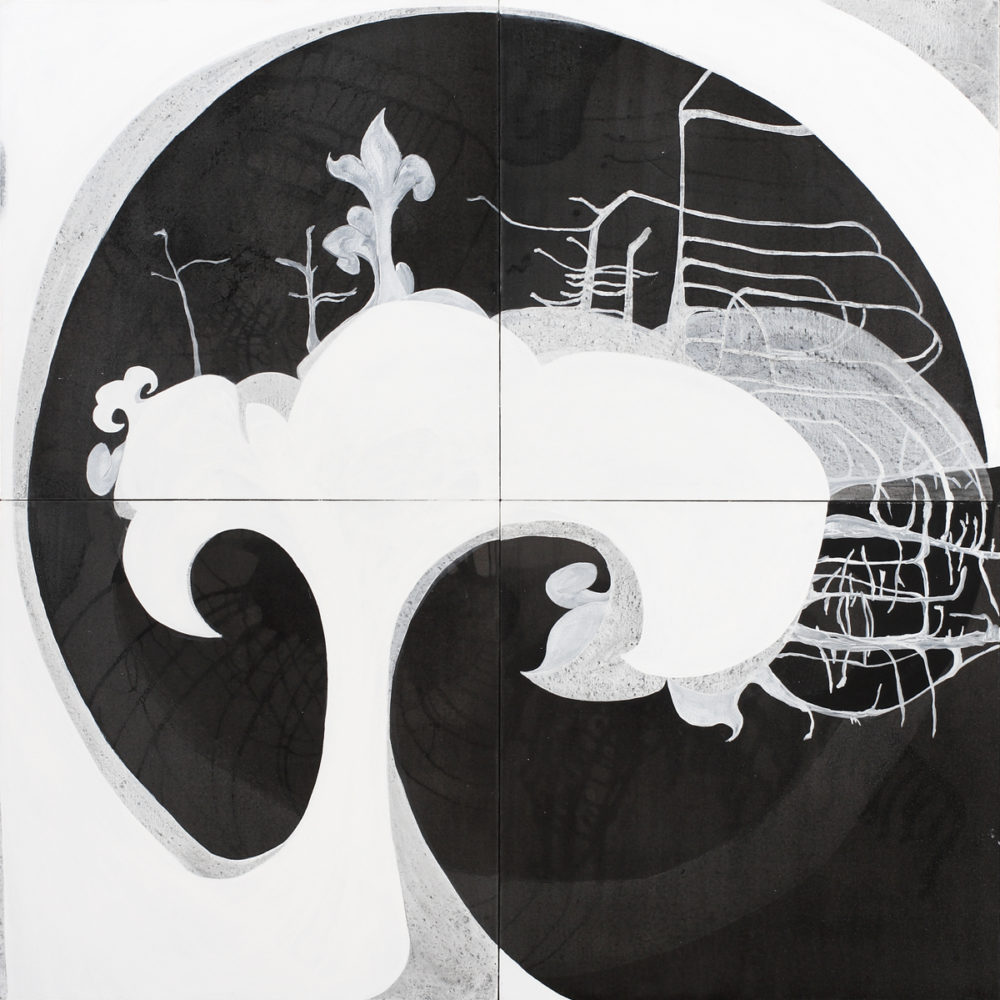

Not My Garden

Jan Manton Art, Brisbane. 2007.

Essay by Jonathan Kimberley

“Why didn’t I become an architect? Answer: Because I thought the blank sheets of paper on which I was to pour my dreams were blank. But after twenty-five years of writing, I have come to understand that those pages are never blank. I know very well now that when I sit down at my table, I am sitting with tradition and with those who refuse absolutely to bow to rules or to history; I am sitting with things born of coincidence and disorder, darkness, fear, and dirt, with the past and its ghosts, and all the things that officialdom and our language wish to forget; I am sitting with fear and with the dreams to which fear gives rise … But in those days I was a resolute modernist who wished to escape from the burden, the filth, and the ghost-ridden twilight that was history—and what’s more, I was an optimistic Westernizer, certain that all was going to plan.” [1] – Orhan Pamuk

This essay has endured a long and winding path to publication, travelling with me embedded in my iBook from Gija Country and Miriwoong Gajerrong Country in the far northwest of Australia, to Meenamatta Country in Tasmania, Limpopo Province in the north of South Africa, Noongar Country in southwestern Australia, and Ngaanyatjarra Country in the Gibson Desert. Like a hybrid organism, it has evolved as an extension of myself, moving amidst the particularly certain uncertainty of globalising postcolonialism.

Landscape

Western conceptions of ‘landscape’ are arguably the most successful, resilient and subversive agents of identity propaganda of modern times; and particularly resilient in Australia because of the overwhelming temptation for the dominant ‘Westernizing’ landscape paradigm for deeply selfconscious re-interpretation, despite well-documented potential for the formation of a more reciprocal intercultural placedness.

The propagation of the imported landscape paradigm has been so effective in creating the identity of ‘Australia’ that at first it seems ‘landscape’ as a word lacks any meaningful contemporary identity beyond describing westernizing urbanity. However at the same time, I believe something about our modern persistence with the landscape paradigm can now also acknowledge and free-up a neglected yet everyday redemptive possibility counterbalancing landscape’s universalising ideology; what I am calling here, the working idea of unlandscape.

In-Between

Artist Dale Frank has said that “landscape is non-representational, it is an abstract concept to all people. It always was a meaning separate from image.” [2] Conversely perhaps, anthropologist Howard Morphy has written, “One of the reasons that the concept of landscape is beginning to prove so useful is that it is a concept in-between. At a time when simple determinisms are breaking down, and the boundaries between disciplines are continually being breached, it is useful to have a concept free from fixed positions, whose meaning is elusive, yet whose potential range is all-encompassing.” [3] Many Australians think this discussion is simply irrelevant, as the land itself and ‘country’ increasingly asserts its quiet presence over the ideological mapping of ‘landscape’.

However, this idea of ‘landscape’ is not so easily discarded; it’s meaning not so easily recast. As Ken Hillis points out in Cartographica (1994), “In it’s coming to be, (landscape) causes the fashioning of a world of distance in order to justify its existence.” [4] As such, by virtue of accepting that landscape is either irrelevant or all encompassing, are we not in danger of further entrenching the very landscape paradigm many romantically think has been discarded along with the old fashioned ‘Australian landscape painting’ tradition?

In 1997, artist and curator Gary Lee said in his essay titled ‘Lying about the Landscape’, “It is blindingly obvious what the function of the (Australian) landscape tradition is: it is about the theft of Indigenous land. It is an artistic representation of, and cultural justification for, the process of colonialism… cultural activity in post-Mabo Australia will be meaningful only if it abandons the legal and cultural falsehoods of colonialism, and practices are adopted to support the political and cultural empowerment of its Indigenous owners. The great Australian landscape tradition? There really is very little to talk about.” [5]

Twelve years after Lee’s statement, despite a burgeoning shift in understanding between the intercultural concepts of Western ‘landscape’ and Aboriginal ‘Country’, the ideological agency of ‘landscape’ remains active despite its theoretical rejection by the postcolonial project. This continues to limit Australia’s ability to reconcile the colonial imperative of the landscape paradigm with its postcolonial intercultural responsibilities.

The Inhabited World

Western conceptions of ‘landscape’ have always been captive of idyllic desires to reduce the complexity of the ecumene (the inhabited world). Indeed, the trajectory of Western modernism can be tracked almost in parallel with that of the Western concept of landscape. In a paper titled Landscape and the overcoming of Modernity (2000), French philosopher, Augustin Berque argues, “…studying landscape, and the ecumene in general, we have to overcome the modern reduction of reality to the real. As physics itself has come to show, the real is unknowable, because it is unpredictable. Reality supposes the real, but also its predication by human existence. Landscape is a perfect example of this complex relationship, and this is why, outstandingly, it shows the way beyond modernity.” [6]

Yet, if showing the way beyond modernity were to become a true capability of landscape, I would argue that it could only be achieved via significant and sustained re-acquaintance with coexistent unlandscape, and in this country, far greater reciprocity and collaboration with Aboriginal Country.

As Ian Mclean points out: “Since its initial formulation in the imagination of European mythographers, the idea of ‘Australia’ has been an agent of deconstruction [to that of Europe]. While we Australians might think Australia is an actual place, it remains a utopian concept (i.e. a no-place), categorically bound like a petulant child to the world it protests”. [7] Western modernity continually attempts to reach beyond itself, to claim the ‘other’ as its own, and ‘landscape’ is one of its most effective means of doing this.

Indeed, the idea of ‘Australia’ is virtually synonymous with ‘landscape’. Thus, in this country, ‘landscape’—particularly when invoked as some sort of universal genre is a foremost obstacle to moving beyond the colonial representation of place. It seems obvious that more complex and reciprocal intercultural relationships with people and Country, specific rather than universal, need to be engendered if Australia is to move beyond the colonial imperatives of Western modernity and its many permutations. Augustin Berque is correct when he says “Landscape is not a universal object” [8]

The Global Universal

Rather than being universal, the landscape paradigm is historical. It gradually emerged out of the largely forgotten Western idea of the ecumene (pictured for example in medieval cartography), which it replaced with a more scientific perspectival vision that informed the European Age of Empire (colonialism, now globalism).

Arguably this reformulation of the ecumene as the landscape paradigm is continuing to be imagined into being as ‘Australia’ today; a contemporary mythical global-village born out of more than a thousand years of dreaming that ‘Westernization’ would inevitably become the global universal.

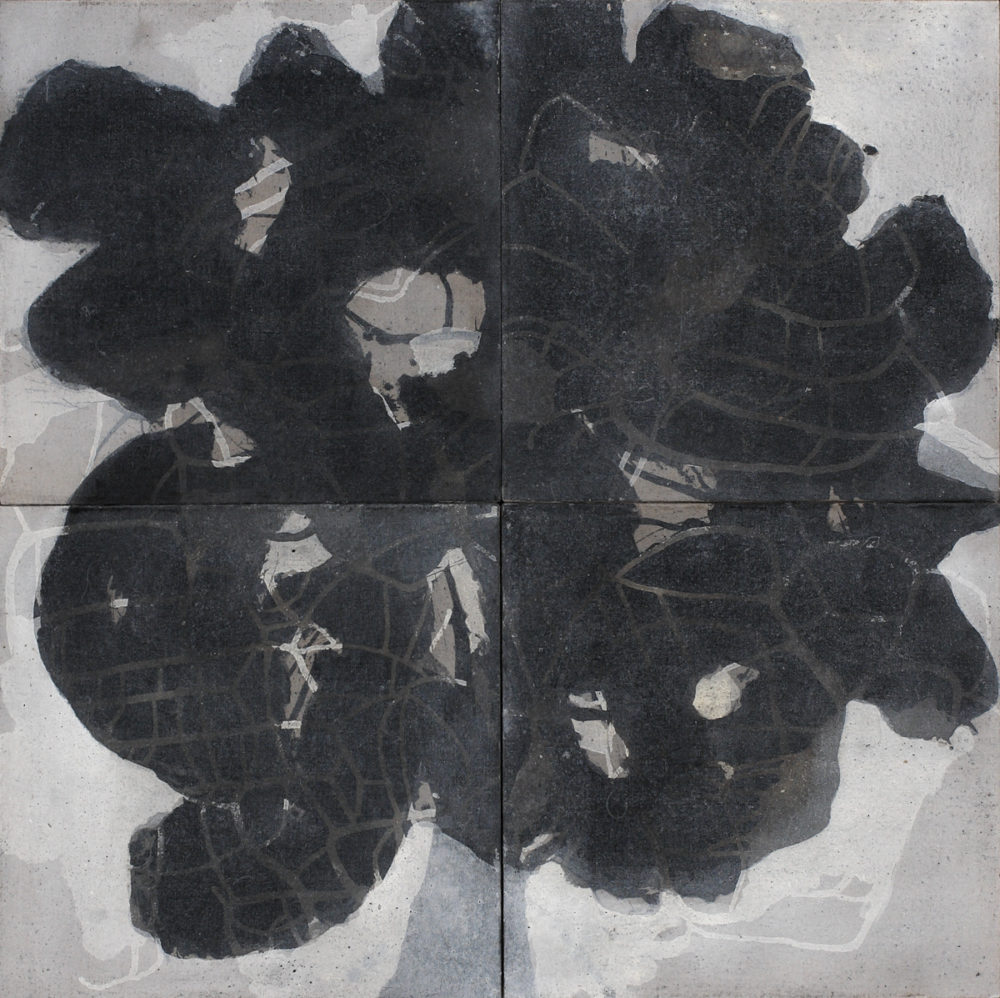

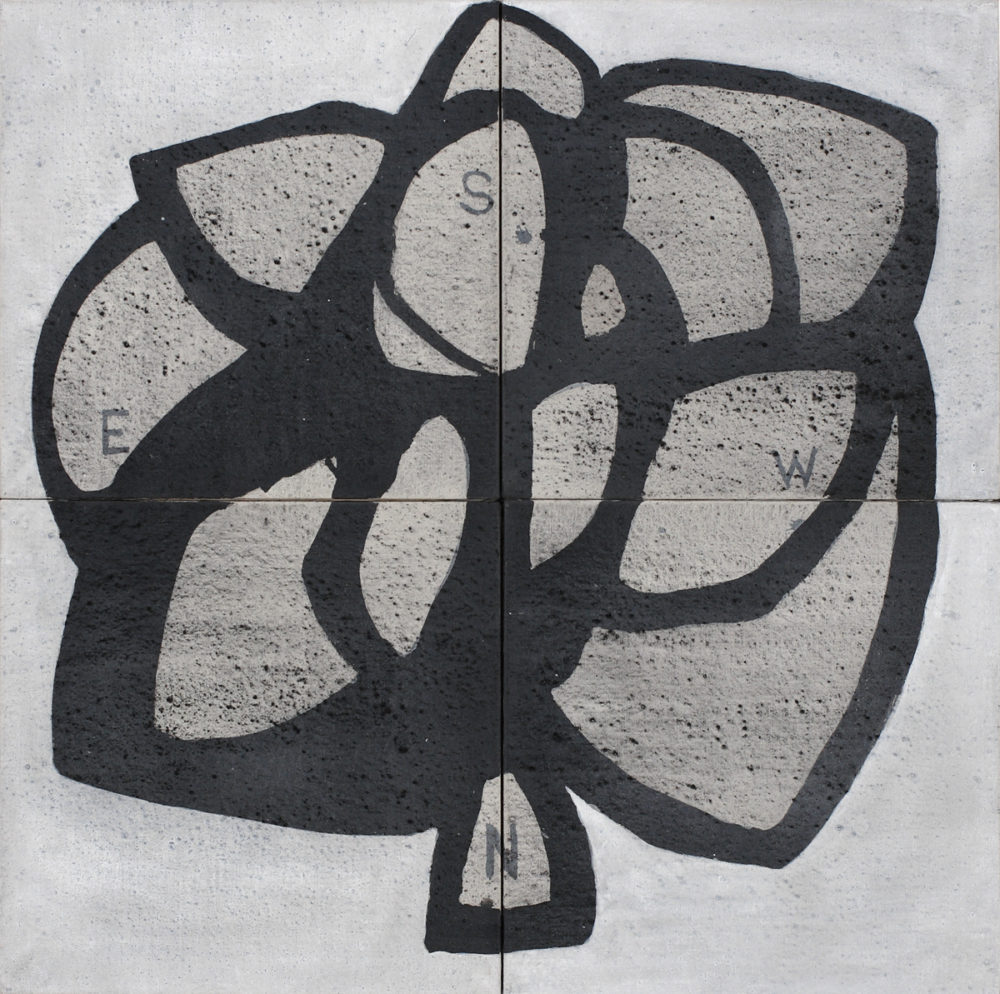

It seems obvious that there continues to be a missing ‘coexistent’ with landscape in this discussion. Since 2005 I have been exploring the idea of unlandscape in my work. Within my recent series of paintings, Not My Garden (exhibited in Brisbane 2007), all paintings are titled Map of Unlandscape in reference to what I see as the potential for new understandings to be drawn from within Western culture, which can enable more reciprocal and productive intercultural discussion.

In this context unlandscape provides an active and intermediary surfactant between ‘landscape’ and ‘Country’, a way of reassessing the Western landscape trajectory amidst shifting inter-cultural understandings of old country in new time.

Rather than redefine the word ‘landscape’ in order for it to accommodate the post-colonial imperative, I propose the delimiting term unlandscape to describe that which is not necessarily bound by the landscape paradigm, but which is coexistent with, and critically aware of, landscape’s inherent (western) cultural agency. Perhaps the working idea of unlandscape can provide renewed investigation of more reciprocal, engaged and open interpretations and conceptions of western culture in this country.

Homi Bhabha says, “The time-lag of postcolonial modernity moves forward, erasing that compliant past tethered to the myth of progress, ordered in the binarisms of its cultural logic: past/present, inside/outside…It is the function of the lag to slow down the linear, progressive time of modernity to reveal its ‘gesture’, its tempi, ‘the pauses and stresses of the whole performance’. This slowing down, or lagging, impels the ‘past’, projects it, gives its ‘dead’ symbols the circulatory life of the ‘sign’ of the present, of passage, the quickening of the quotidian.” [9]

Perhaps it is the “time-lag” of unlandscape which is the agency now required to move through the post-colonial gaze of Australia, in recognition of the inherent complexity and multi-nation “fact-reality” [10] of Aboriginal Country. At once grounded in adaptation, and ambivalent toward new ghosts of post-colonialism, unlandscape continues to be resolute and coextensive despite the continuing Australian desire for subversive ‘blank sheet’ recreation of Country in the image of the landscape paradigm.

This Country is not my garden. And I cannot claim that the propagation of the landscape paradigm in this country is not my garden, either. This coextensive acknowledgement—not my garden (landscape : unlandscape)—breaks open a more reciprocal dialogue between ‘landscape’ and Country; effectively delimiting the way into, what might now be called, the Exmodern. [11]

Essay by Jonathan Kimberley (2007).

© Jonathan Kimberley, 2007.

[1] Orhan Pamuk, Why Didn’t I Become an Architect?, in Other Colours, Essays and a Story, Alfred A Knopf, Random House, New York, 2007, p.307

[2] Dale Frank, article by Ashley Crawford, Art and Australia magazine, Vol42 No2, 2004 p207.

[3] Howard Morphy, Colonialism, History and the Construction of Place: The Politics of Landscape in Northern Australia, in Barbara Bender, ed., Landscape: Politics & Perspectives (Oxford: Berg, 1993).

[4] Ken Hillis, The power of Disembodied Imagination: Perspective’s Role in Cartography, Cartographica Vol.31 No 4, 1994, p.11.

[5] Gary Lee, Lying About The Landscape, in Lying About The Landscape, Ed. Geoff Levitus, Craftsman House, 1997, p110.

[6] Berque, Augustin, The Cultural Approach In Geography—Landscape and the overcoming of modernity—Zong Bing’s principle, Seoul, August 14-18, 2000 from Abstract of Ecumene: An Introduction to the study of Human Milieux, Belin, 8 rue Férou, 75006 Paris, France, 2000.

[7] Ian McLean, The Necessity of (Un)Australian Art History for the New World, Artlink, Vol 26 no 1, 2006.

[8] Berque …….ibid

[9] Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, Routledge, New York, 1994. p. 246.

[10] Letter from Jim Everett to the author, 16th March 2007.

[11] The concept Exmodern is the subject of the authors forthcoming collaborative conference paper titled Working Exmodern, to be presented with Jim Everett at the 2nd International Imagined Australia Research Forum in Italy 2009. It is also related to the authors forthcoming MFA thesis, University of Western Australia.