Oculus

Bett Gallery Hobart, Tasmania. 2011.

Essay by Helen Norrie in discussion with Jonathan Kimberley

Looking through a window originally defined the Western picturesque conception of landscape as a perspectival view received by the eye. However our eyes are not merely glass windows, they are oculi, which are open to all of the elements, not just what is seen. We see with our eyes and our imaginations, but also by our actions or experience in place and time, and the way we relate to each other is the fundamental basis of the concept of worlds.

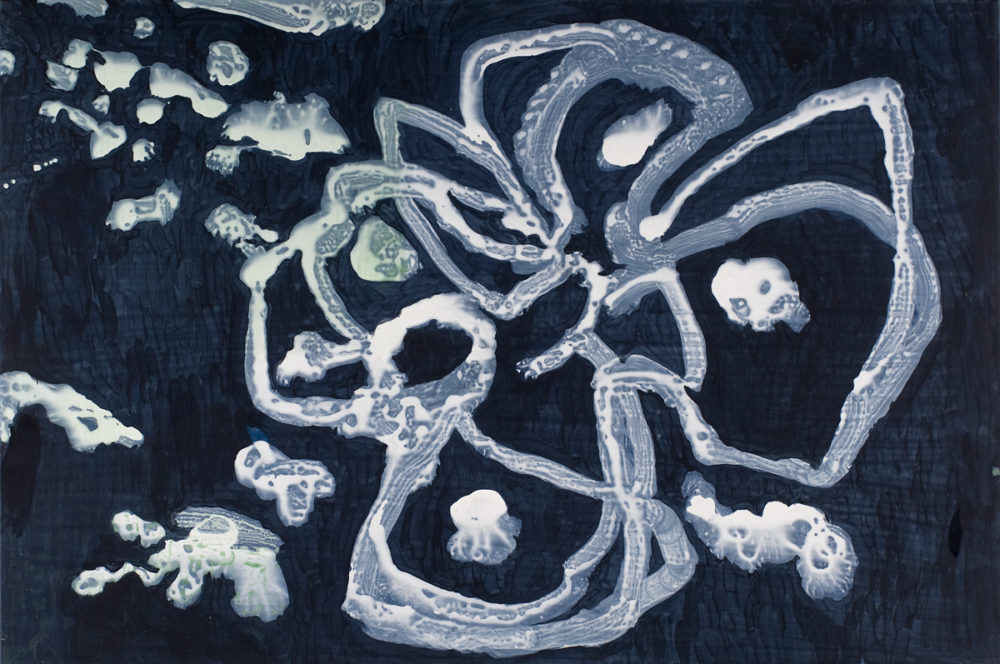

Oculus is a series of paintings emerging primarily from Rome and Valcamonica in northern Italy that expands the simple duality of ‘seeing and being seen’; looking beyond the notion of oculus as simply an eye or an aperture. Oculus draws directly on specific sources: ancient rock engravings of Valcamonica, a pair of mountains that overlook the region, the Pantheon in Rome, and more specifically the oculus of the Pantheon. Two particular rock engravings are directly referenced: the iconic Rosa Camuna, which has become the symbol of the region of Lombardy, and a second image that can be understood as one of the oldest known world maps (Mappa del Mondo) in Europe.

Oculus is inherently linked to Kimberley’s interest in maps and mapping, particularly depictions of territory described in ancient world maps that present a totalizing image of a world that cannot necessarily be seen. World maps describe much more than just topography or geography, they conceptualize the relative position between one locality or identity and another, creating a sense of context and expressing the immersive reality of living in the world. This recognition of the broader context beyond – of one’s position in relation to other places and people – represents for Kimberley a timeless interest in globalism and an enduring awareness of “seeing and being seen, not only by each other, but also by the systems within which we dwell.”

The desire to capture an understanding of a place and to communicate this to others is common to both cartography and landscape painting. Maps reflect a shifting understanding of the totalizing idea of place, and a survey of maps and mapping techniques across time reveals a fascinating array of depictions. Maps vary from conceptual diagrams to pictorial scenes that are often neither to scale nor in proportion. However, like landscape painting, even accurately surveyed and precisely drawn maps are interpretative, as they abstract detail and prioritise specific elements, patterns or relationships.

These ideas are expanded in Kimberley’s work in which the idea of Oculus can be understood in multiple ways. Like the world map, the view down through the oculus at the apex of the Pantheon provides a totalizing view, while from below it acts as an aperture that looks out toward the limitless expanse of the heavens. However, this oculus is more than a two-way window to the world, it presents an intriguing paradox. The circular ring beam that forms the oculus is an essential element of the structural integrity of the building, but it also creates a hole that allows the dynamic unpredictability of nature to penetrate the precisely ordered interior. The oculus invites the rain and the sun into the centre of the building, and this creates an interplay of shadow and light that distorts the perception of the perfect geometric form of the coffered dome, overlaying a shifting ambiguity and uncertainty; dissolving duality into active spatiality.

landscape

“…the panoramic view furnishes a more detached and picturesque perception that turns the [place] itself into an exhibit to be consumed visually and from a distance. This perspective renders the viewer at once a reader and godlike…” [1]

Embracing the panoramic view, western landscape painting creates a distancing effect that objectives and disconnects the viewer. The perspectival characteristics of specifically constructed ‘scenes’ heighten the sense of foreground / middle ground / background, reinforcing this sense of distance. In contrast, the idea of the picturesque in landscape architecture offers other possibilities for establishing more dynamic relationships between the viewer and the view, and between people and a place. Although the idea of the garden as a ‘setting’ is fundamental, picturesque landscape architecture is underpinned by two specific strategies that engage the viewer more directly. Static scenes are juxtaposed with sequential movement, and ontological relationships are established through allegorical references.

Firstly, the formal structure of the garden is orchestrated from the point of view of the experience of a person moving though the landscape, with specific objects – trees, hills, follies – places as part of the series of constructed ‘scenes’ that come into view along this journey. Each is seen from different perspectives and at varying distances as the visitor follows the prescribed path. Secondly, the natural environment was regarded as an “armature or frame upon which to drape or construct known aesthetic characters”.[2] Follies were designed in specific styles, which represented certain allegorical ideas (or ideals), engaging with the notion of association or “the ability of a design to raise in the viewer a train of ideas”[3]. In some gardens, this emblematic use of association was also contrasted with a desire to provoke the imagination in terms of ‘sensibility’, through the use of natural elements – particularly water – to express particular ‘moods’.

Whilst deliberately ‘un-picturesque’ nor portraying ‘scenes of landscape’, Kimberley’s work is inherently linked to deeply ingrained picturesque traditions, both in Western painting and in landscape architecture. However, Oculus questions and juxtaposes these ideas. Rather than a preoccupation with an established sense of form and order, and a focus on the pictorial image of the static scene, Oculus explores other intentions. By creating images that are the result of the dynamics of movement and experience, and by embedding meaning through the use of symbolic or emblematic elements that draw together broader references, Kimberley seeks to articulate the dynamic spatiality, a condition of human inbetweenness that he describes as, “the conceptual oculus between the nature of country (Paese) and the architecture of landscape (Paessagio).”

being there

“To at least some extent every real place can be remembered, partly because it is unique, but partly because it has affected our bodies and generated enough associations to hold it in our personal worlds.”[4]

In the wake of modernism, particularly the mechanistic fascination with buildings as ‘machines for living’ Kent Bloomer and Charles Moore’s seminal text Body, Memory and Architecture (1977) highlighted the significance of haptic experience, which involves perception through touch, and the position and movement of the body in space. Emphasizing movement as an essential aspect of experience drew attention away from the ‘image’ of architecture, counteracting a preoccupation with style and form. Bloomer and Moore argued that the whole body was at the centre of experience, not just the eyes and ears, and that engaging with the haptic senses addressed the three-dimensional and temporal nature of architectural experience.

Considering a building in terms of experience, rather than as a static object, prioritizes the role of the building as a site of primordial movement. The basic elements of columns, walls and roof are imbued with meaning as much through the memory of use and ritual as through codified, stylistic form. The ‘constant dialogue’ created by movement emphasizes dynamic relationships, or the spatiality of architecture that is evoked through experience. I would like to suggest that the concept of architecture may be substituted with the concept of landscape, and that implicit in Kimberley’s paintings is the insistence that landscape is not just visual, but also experiential.

Oculus foregrounds the idea of such spatiality as a dynamic relationship, and the work seeks to express the experience of being there, in the landscape, rather than looking over or at. This understanding is directly influenced by Kimberley’s collaborative work with Indigenous Australian artists, including with puralia meenamatta (Jim Everett) in meenamatta country in Tasmania (2006) and with Kayili artists at Lake Kuluntjarra in the Gibson Desert in Western Australia (2009). These collaborations involved spending time ‘in country’: engaging with the place through working and being there together. Kimberley believes this is a relationship of far greater import than the previous landscape modus operandi of painting en plein air.

Oculus explores the experience and meaning of the place to culture, offering up experiential palimpsests of what Kimberley calls ‘unlandscape’. This understanding of the experience of the place is central to all of Kimberley’s work, which expresses the rhythm of dynamic relationships inbetween people and place. Oculus embraces both abstraction and multivalent amorphous figuration as a direct result of looking closely at hundreds of rock engravings in Valcamonica. Although the work is partly symbolic, it is essentially experiential and expressive, rather than overtly esoteric or pictorial. The spatiality of these paintings cannot be categorized or defined as either landscape or country – or architecture.

Rather than portraying images of Italian landscapes, Oculus presents paintings about ‘being there’ in Valcamonia, amongst the mountains and the rock engravings. Each painting recalls the dynamic relationships incited by experience. Oculus reminds us that just as we leave a physical trace – footsteps, rock engravings or buildings – so too being there also leaves an impression on us, and this mirrors the reciprocal idea of the oculus, which both sees and is seen.

afterimage

“…an ‘iconography of intervals,’ it is something of a hermetic mise en scene of the formal continuities between images and objects…a critical (and symptomatically modern) moment in which human intelligence turns itself into its own object of study, probing its limits and those aspects of reality that its discourses can no longer grasp.”[5]

Underpinning Oculus is the idea of the ‘afterimage’ – the impression of a vivid visual sensation that is retained after the stimuli have ceased. The afterimage is not what you actually see. It’s not the pictorial semi-photographic image, but the residual image that remains etched on the back of your retina once you turn and walk away. However, in Oculus the notion of afterimage refers not only to the residual visual image, but also the overall residual experience of journeys in Italy and Australia, and of previous collaborations with other artists. The solo paintings in Oculus are therefore afterimages of all these experiences, distilled for Kimberley during residencies in Valcamonica. As Kimberley describes:

“These works are part of the continuum of my personal artistic explorations (both solo and collaborative) over the past few years, during which I have been consciously attempting to push landscape painting beyond what I call postlandscape; which is itself an afterimage of the Western conception of landscape. Oculus resists any ‘grand narrative’ in favour of whatever ‘afterimage’ forms in the here and now.”

Although each of the paintings in Oculus are of actual places, they are not panoramic images, rather they present a series of afterimages that express the residual experience and memory of being in a place rather than a pictorial depiction of the landscape itself. In many ways the paintings can be decoded through the recognizable symbols which recur in several woks, and in other ways they are more abstract experiential palimpsests that are read as afterimages.

The partially eroded traces of ancient rock engravings are a form of afterimage: what remains centuries on is merely a fragment – both actually and conceptually. We can’t quite see it, or understand it, but we can recognize the innate human desire to communicate an understanding of place and experience that is common to all cultures across time. It is a trace that is recognizable, yet ephemeral, distinctly unique and intangible. The afterimage resonates and reverberates, distorting lived experience into fragments, and inviting interpretation.

The afterimage is one thing at its inception, and constantly changing as it recedes, or is recalled. It is in constant flux. No one person’s afterimage is the same as anyone else’s. Within Oculus some of the afterimages are engraved like tattoos and others are fleeting, like rain eroding a ten thousand year old rock engraving. Attempts to explain or delimit what the work is about are nullified by the inherent impossibility of pinning down a universal understanding of an afterimage, which is precisely the beauty of the perpetual dynamic of the ‘iconography of intervals’; the essential ‘inbetweenness’ that this work embraces.

inbetweenness

“… memory is not just information that individuals recall or stories being retold in the present. It is not layered time situated in the landscape. Rather, memory is the self-reflexive act of contextualizing and continuously digging for the past in the present…” [6]

A Pantheistic temple is inclusive and totalizing, open to all the worlds’ beliefs, and accepting of all Gods. The Pantheon suggests a metaphor for the ‘inbetweenness’ within the human consciousness, an inherently intercultural and increasingly global spatiality, which these painting evoke.

The ‘world map’ or Mappa del Mondo engraving in Valcamonica bears a striking resemblance to the twin-image of the perfectly round oculus of the Pantheon and the irregular light shadow that is cast as the sun projects through this aperture onto the coffered semi-circular domed ceiling inside. Similarly, the Mappa del Mondo depicts a pathway leading off to a satellite world that may be interpreted as the sun, the moon or an unknown land within the universe. Within the twin-image this pathway (and the pantheistic light shaft) evoke the spatiality of the inbetween.

Rock engravings can be understood as oculi. The surface has been chipped away and the engraving allows the viewer to literally see into the rock, and also to metaphorically look down into country/land. Kimberley suggests that understandings of European rock art are limited when these images are categorized as prehistoric, rather than also interpreted and understood as contemporaneous. He contests that this view is influenced by persistent Western evolutionary ideologies that consider time as linear, rather than cyclical and seasonal. Relegating these images to history negates the potential of understanding dynamic relationships between past and present. Rock engravings continue to confound researchers as all great art does, and these ancient images embody inbetweenness, exploding preconceptions of temporal linearity.

Within Oculus the interplay between abstract and symbolic or figurative elements allows the work to be read in myriad ways, further implanting these ephemeral notions. Oculus, Pantheon, Rosa Camuna and Mappa del Mondo are embedded and layered within the paintings: emblematic graphics that create allusions to a complex array of ideas. Although some of these forms are reinterpreted and can be recognized in the paintings as symbols, they are not intended to be representational. From the graphic layering of these elements emerges the spatiality of afterimage and inbetweenness.

There is a recognizable formal relationship between the repeated clover-like graphic of the Rosa Camuna and the glyph-like elements in many of Kimberley’s earlier works. He is intuitively drawn to this form in the same way that we connect with our distant cultural relatives with whom we share genetic similarities and/or common experiences. Although the Rosa Camuna is an ancient symbol, it has contemporary resonance as it continues to provoke unanswered questions about what it is communicating. The form of Rosa Camuna can be interpreted as a type of compass, which implies an implicit sense of continual re-orientation. The title of Oculus: Tutti i Sensi (Rosa Camuna), meaning simultaneously all directions and all the senses, suggests this idea.

Oculus recontextualizes these images and the experiences provoked by seeing the rock engravings and the place in which they were made, erasing the divide between ancient, classical, and contemporary eras, dissolving the linear idea of evolutionary time.

In some works the forms of the rock engravings are immediately recognizable, and in others any trace is exploded to the point of total dissolution. These images feel like the future to me. Some seem more sore sci-fi and perhaps extraterrestrial than others, which are definitely grounded in something real or ‘of this earth’ rather than the otherworldliness of a future place in time and space.

Within each painting there is a continual shift in scale from near to far, and dynamic shifts from animate to inanimate. Overlaid with filigree that can be understood as circuitry or snow, Oculus: Orographico, 2011 and Oculus: Monte Concarena, 2011, expand, disintegrate and shift like moving weather or clouds generated by the mountains themselves. Embedded amidst the glyph-like pattern, and enmeshed within the finely figured tracery, blocks of colour – white, yellow, pink, blue – evoke the active spatiality of the ‘inbetween’. The space within the circuitry is as significant as the trace that defines it. It is clearly not empty – it is colour that is alive. There are millions of such active spatialities in the paintings, both consciously inscribed and intuitively implanted.

Creating connections across time and place, Oculus draws on the global reality that we are at a critical point of embracing intercultural understanding, and finding new ways of seeing through our own cultural lenses. Oculus refocuses and welcomes this.

Essay by Helen Norrie in discussion with Jonathan Kimberley, nipaluna (Hobart) Tasmania, March 2011.

© Jonathan Kimberley & Helen Norrie (2011).

Special Thanks: Helen Norrie, Federico Troletti, Elena Mauri, Centro Camuno di Studi Preistroici, Alberto Marretta, puralia meenamatta Jim Everett.

[1] Giebelhausen, Michaela. 2003. ‘The architecture of the museum: symbolic structures, urban context’ in Critical Perspectives in Art History, Edited by T. Barringer, M. Meskimmon and S. West. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

[2] Meyer, Elizabeth. 2005. ‘Site Citations: The Grounds of Modern Landscape Architecture’ in, Site Matters: Design Concepts, Histories and Strategies, edited by C. J. Burns and A. Kahn. London: Routledge, p. 103.

[3] Archer, John. 1983. The Beginnings of Association in British Architectural Esthetics. Eighteenth-Century Studies 16, (3):241-264, p.243.

[4] Kent C. Bloomer & Charles W. Moore, 1977, Body, Memory and Architecture, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, p.107.

[5] Oramas, Luis Perez, 2006, An Atlas of Drawings, Museum of Modern Art, New York, p. x.

[6] Till, Karen E. 2003. ‘Construction Sites and Showcases: Mapping The New Berlin through Tourism Practices’ in, Mapping Tourism, edited by S. P. Hanna and V. J. J. del Casino. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press.