Tremezzo

Bett Gallery Hobart, Tasmania. 2013

“We have no word for this darkness. From time to time we all come across this darkness, seeing everything: so much everything, that we can distinguish nothing. It is not night and it is not ignorance, it’s the extension from which everything came.” [1]

– John Berger

My working travels in northern Italy have led me to thinking anew, particularly around what John Berger eloquently describes (above) as the inherent spatial darkness within and surrounding early European rock art; and by extension, the Indigenous origins of the European concept of ‘landscape’.

Similarly, my working life in northern Australia has increased my awareness of the difficult cultural interiority that ‘landscape’ so uncomfortably deploys here. In Australia the ‘landscape’ genre has been so expanded and conflated to the point of purporting to be not only the pre-, but also the ‘post-Aboriginal’ [2] imaginary; a conceptual disconnect, laid out over what has always been an inherently Indigenous multi-national country. It’s the seemingly benign contemporary nature of this perpetual disconnect that Tremezzo examines from an originary European cultural perspective.

In Italian, ‘tremezzo’ loosely translates as ‘three and a half’. Globally, three and a half minutes is the average attention span given to a contemporary song, or to a you-tube video. It’s the longest time most people can hold their breath… In the context of this exhibition, Tremezzo suggests that contemporaneity [3] in the information age is inherently intercultural and exists, perhaps most potently, within the first three and a half minutes after a certain experience. Tremezzo examines the idea that an ‘afterimage’ might offer a new and vital portal of intercultural insight.

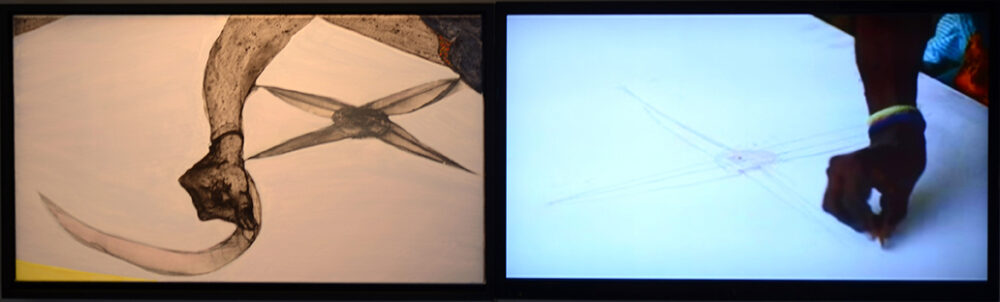

Tremezzo is a series of 3½ minute videos & charcoal drawings/paintings on linen, and an ephemeral wall drawing/video projection developed over 3½ nights, probing the interiority of the ‘afterimage’ and the contemporary ‘landscape’ disconnect in a new way. The works are presented as diptychs – both the video screens and the paintings are the classic landscape, 32”, 16:9 format. The videos were made in the small village of Tremezzo on Lake Como in northern Italy, and in Gija country near Warmun in the north of Western Australia.

An ‘afterimage’ is usually considered to be the ephemeral, hovering, often inconsequential, remnant of ocular vision that remains in the minds-eye for just moments after one looks away. In this series however, I’m interested in the idea that afterimages might also exist in other ways, and be capable of re-illuminating inherent intercultural knowledge, within the spatiality of cultural difference; the ‘darkness from which everything came’.

So how might this oblique form of dreamlike memory be re-visioned so as to evoke potential new understandings of such spatiality? At first glance, the idyllic ‘afterimages’ in Tremezzo, reflect classic aspects of the contemporary ‘landscape’ paradigm. Both the historical substance and the contemporary veneer of ‘landscape’ as ‘a way of being’ and interacting in the world, are indelibly connected to contemporary intercultural spatiality. The landscape view itself, mediated by the classic 16:9 screen, is actually a deliberate reduction of the original. Ever-since the earliest known artistic shift to ‘representing’ aspects of landscape in Europe – seen for example in the (8th – 3rd Century BC) rock engravings of Valcamonica in northern Italy – some of which are among the oldest known maps in Europe – ‘landscape’ has been subjected to both a continuous reductionism and expansion. Yet the contemporary format remains: the ‘landscape’ media screen, the window, the wall, the room, the paddock, the view, the restricted spatiality.

The landscape paradigm began as an unlimited flow, an open source, rock engravings – in Italian country (terra). Deliberately however, Tremezzo doesn’t directly reference rock art at all, either in Italy or Australia, because it is the more contemporary delimiting incarnation of the landscape paradigm that I’m returning to in this series – the cumulative afterimage of landscape as a contemporary concept – the spatiality whereby such idyllic cliché pushes back into real life – the sense of loss engendered and the sense of potential that remains. Yet, indirectly the influence and trajectory established by what is some of the oldest known European art – the rock engraving maps of Valcamonica – perfectly confirm the idea of the ‘dark inner-light’ which Berger describes. The landscape paradigm is both a product of, and a hinderance to, seeing this particular kind of darkness in daylight; a way of seeing into the interior spatiality between cultures, countries and oneself – over again. Tremezzo asks, do ‘we’ of European descent have the ability to see into the present within the spatiality created by the afterimage of landscape, in more interculturally relevant ways? Or does ‘landscape’ nullify its presence?

Anish Kapoor’s famous dark-light pigment-in-wall works, such as Void (1989), evoke a related contemplative and interactive inner spatiality, an ‘intervention’ in the architectural landscape of the white cube – whereby the work in it’s cultural space evokes a powerful feeling of interiority in oneself. Yet, despite what could be described as his eponymous landscaping machine, My Red Homeland (2003), currently operating literally around the clock, carving out mountains and valleys at the MCA in Sydney, Kapoor says, “I have nothing to say as an artist” [4]. Speaking for itself then, the work is perpetually pushing what might be interpreted as the global fat of ‘landscape’ to the rim, forming mountains and valleys, a desert in the centre, clearly referencing the dominant global perception of the linear time of ‘landscape’ – the great delimiting factor in global westernization.

Londoner Kapoor was born in India, but this only further illustrates how the globalizing phenomenon of landscape is continually responsible for the reductionism of particular types of intercultural afterimages. And, as this kind of postlandscape [5] art continues to make clear, the concept of intercultural appropriation itself; the global phenomenon of the reduction of intercultural complexity to the spatiality of ‘landscape’.

In some ways, Tremezzo seeks to be the opposite. A deliberate return to a very direct consideration of the contemporary, global and historical conceptions of the postlandscape era; the spatiality between landscape video and painting.

While the videos and paintings in Tremezzo are ‘afterimages’ of intercultural trajectories formed over millennia, they more deliberately reference the ‘surface’ nature of landscape as both a conceptual and material life-practice in recent European history. The three and a half minute videos on repeat and the freehand drawings on canvas in direct response to the videos, combine as ephemeral afterimages made visible – illustrating a kind of cyclical betweenness and the difficulty encountered when seeking unlandscape. Afterimages distilled,they attempt to reference a spatiality outside the linearity of landscape time, but are also beholden to the landscape paradigm, evoking but not quite able to reach, the interior darkness that is the source of light…remaining an illusion. Kapoor appears to reach it, and yet his reliance on perspectival optical illusion – essentially the same effect employed throughout the history of landscape – remains the delimiting factor in his works’ ability to find the ‘dark way in’ anew. It’s a common ailment.

Seeking gaps through the veneer of contemporary postlandscape is an almost universal attempt at new intercultural insight. Recently in an article titled, ‘Does Tasmania need an intervention?’ Natasha Cica cites the well-worn Leonard Cohen quote, “there is a crack in everything – that’s how the light gets in.” [6] Yet curiously, the welcoming of such new light, whether in Italy or Tasmania, remains the greatest challenge for perspectival ‘landscape’, whether breaking out of single point perspective, or through a more diffuse global perspective. As one of my nomadic homes, Tasmania is both a key outpost and absolutely central for me in this discussion. In many ways, Tremezzo was born in Tasmania. The Alcorso Foundation Italian Residency (2009) enabled me an extended journey in Italy (2009), to investigate the origins of Indigenous European landscape and mapping. My ongoing collaboration with puralia meenamatta (Jim Everett) is also continuously instructive. And Tasmania is arguably the originary home of Australian ‘landscape’ art.

When the Romans invaded what was later to become northern Italy, the Indigenous Camuni people had already been creating the most exquisite rock engravings that today continue to both relate and conceal their complex and contrary knowledge of country (terra). And, it was the arrival of these landscaping forces from the south that brought irrevocable change to the valleys, with overlaid and lost concepts of belief, identity and knowledge. The interplay and overlay of such landscape (paessagio), over land (paese), is a global phenomenon. Between 5 and 10 thousand years ago in northern Italy, glaciated granite was the media ‘screen’ of choice on which rock engraving emerged as the dominant art form of its time; the origin of landscape itself as an interactive concept and practice. To this day however, the delimiting nature of landscape thinking continues to prevent a full interaction with the inner-darkness of the rock; some say the incisioni (engravings) are the way back into this inner spatiality.

By seeking this almost lost spatiality, in the everydayness between video and painting, Tremezzo is also asking: what is the difference between an ‘afterimage’ and an appropriation? Is it that ‘appropriation’ not only limits our participation, but also now defines global contemporaneity? Whereas, an afterimage maintains the capacity to reveal previously unseen intercultural connectivity? Could afterimages therefore reveal that appropriation has always defined the delimiting cultural concept of landscape?

A simple drawing based on a three and a half minute video. Time passing with an everyday picnic on Lake Como. A discussion across the gallery with the everyday moment (over the same time span) of Gija artist Mabel Juli making an exquisite charcoal preparatory drawing for her eponymous Garngin and Wardarl (Moon and Star) Is the video an afterimage, or a poetic appropriation? Is the drawing of the video an appropriation and hence the reductionist westernizing role of the afterimage? Or do the two afterimages combined – draw out another way of re-entering the discussion? Are they both, by virtue of their re-framing within a screen, reduced to landscape? Or could such an afterimage be a contemporary way of seeing into ‘the darkness that is not ignorance’?

Berger says, “It doesn’t matter what size we are when we nudge the surface: we may be gigantic or small – all that matters is how far we have come through the rock.” [7]

© Jonathan Kimberley 2013.

Special Thanks: Mabel Juli, Warmun Art Centre, Elena Mauri, Federico Troletti, Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, Foresteria Nadro; Camilla Franzoni.

[1] Berger, John, The Shape of a Pocket, Vintage International, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2009, p.37. NB: Berger describes his thinking in relation to the famous Chauvet Cave paintings, in France.

[2] See: Kimberley, Jonathan, discussion around Imants Tillers’ concept, ‘Not yet post-Aboriginal’, Kuluntjurra World Map : The Nine Collaborations, exhibition and thesis, MFA UWA, 2010

[3] Terry Smith, has written extensively on contemporaneity. See for example: ‘Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity’, Critical Inquiry 32 (Summer 2006), 2006, The University of Chicago. pp.681-707.

[4] Allen, Christopher, ‘Spiritual paradox at play in the work of Anish Kapoor ‘, Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, The Australian Newspaper, Arts, 2 February, 2013.

[5] See: Kimberley, Jonathan, Kuluntjurra World Map : The Nine Collaborations, exhibition and thesis, MFA UWA, 2010.

[6] Cica, Natasha, ‘Does Tasmania Need an Intervention?’, The Conversation.edu.au, https://theconversation.edu.au/does-tasmania-need-an-intervention , 4 February 2013.

[7] Berger, John, The Shape of a Pocket, Vintage International, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2009, pp.41-42.